FDI screening in Norway: five take-aways from the Bergen Engines case

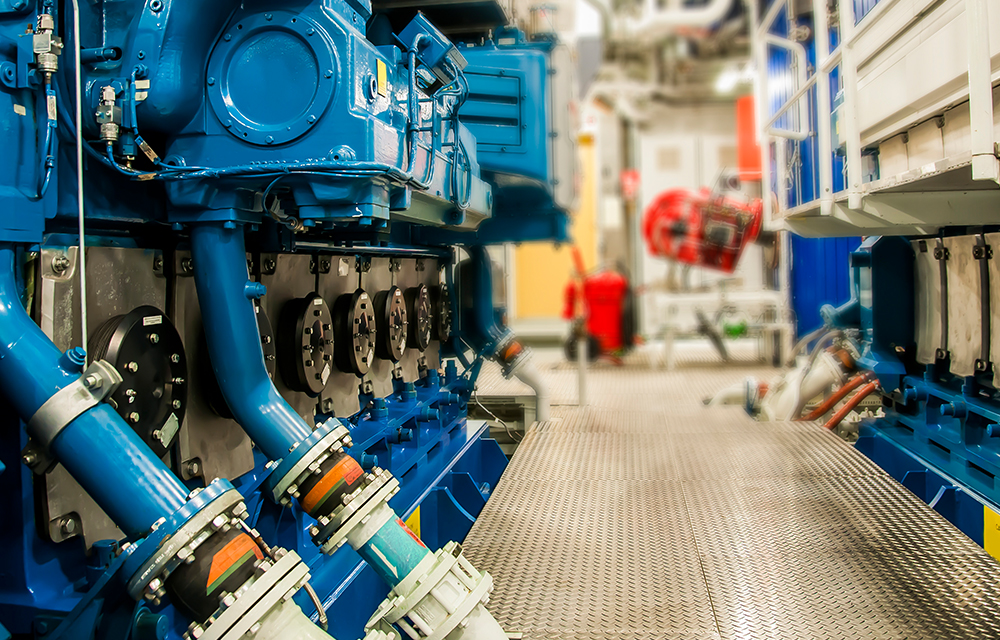

On 23 March, the Norwegian Government announced its decision to block the sale of Bergen Engines, a supplier of marine diesel engines, to a Russian-controlled buyer. The case is the first of its kind in Norway, but it will almost certainly not be the last. Here are some points worth noting for M&A transactions involving Norwegian targets.

On 23 March, the Norwegian Government announced its decision to block the sale of Bergen Engines, a supplier of marine diesel engines, to a Russian-controlled buyer. The case is the first of its kind in Norway, but it will almost certainly not be the last. Here are some points worth noting for M&A transactions involving Norwegian targets.

Investment screening in Norway is not limited to the targeted notification regime. Norway’s 2018 Security Act introduced a targeted regime for notification and review of certain investments. As described in an earlier Haavind update, these rules only apply to acquisitions of qualified ownership interests in companies subject to the act by way of an individual decision from the authorities. Such decisions may be issued to companies which i.a. own assets or are involved in activities deemed essential to national security interests.

As no such decision had been taken for Bergen Engines, the targeted screening regime was not applicable. However, the Security Act also includes a separate provision which grants the government a general power to take decisions deemed necessary to prevent activities presenting a not insignificant risk of a threat to national security interests. The government has now, for the first time, made use of this provision to block a foreign direct investment.

The case illustrates that the Norwegian Security Act has a two-pronged system for investment screening consisting of targeted screening rules supplemented by a general power to block any investment that gives rise to a sufficient level of risk related to national security.

The decision was based on traditional national security concerns. While there are examples in other European countries of investment screening regimes being expanded beyond matters of national security, the government’s conclusion was firmly rooted in traditional national security concerns. The government in particular referred to the risk that Russia could get access to know-how and technology of strategic importance, which could strengthen Russia’s military capabilities in conflict with Norwegian and allied security interests. In addition, it was deemed important to uphold the effectiveness of the sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014. Russia has, due to these sanctions, experienced difficulties with accessing the technology in question.

The buyer’s alleged connections to Russian authorities played a key role. Although the buyer, TMH International, is not directly controlled by the Russian state, the owners’ alleged links to Russian authorities was highlighted by the Norwegian government. It seems reasonable to assume that buyers which are owned by states which Norway does not have any security cooperation with, or buyers with links to the governments of such states, will face a higher risk of intervention when investing in companies considered important to national security interests.

The review timetable is uncertain. While the targeted investment screening regime mentioned above provides for a review period of 60 working days, the provision applied in the Bergen Engines case comes without any formal rules on the review process. The Norwegian government was given advance notice of the sale in December 2020. In M&A transactions where prior contact with the authorities is advisable, it is therefore important to consider the risk of a prolonged review process.

The case could affect the on-going assessment of the rules for foreign investments. In a statement regarding its decision to block the sale of Bergen Engines, the government emphasized that an assessment of the Norwegian investment screening rules had already been initiated prior to this transaction. In this context, the government has made it clear that it will seek to cooperate more closely with the EU going forward. Although EU Regulation 2019/452, which establishes a framework for national screening regimes and a cooperation mechanism, is not directly appliable in Norway, the government may consider proposing more detailed screening rules comparable to those which have recently been enacted or expanded in a number of member states.