New state aid framework may speed up investment in offshore wind power and other renewable energy production

The new framework opens the door to increased public financing of investments to accelerate the transition towards a net-zero economy, including in renewable energy production, and represents some of the most radical changes in European state aid law ever seen. Importantly for Norway, the framework expands the scope for granting state aid to new wind power projects.

Overview

In March 2023, the European Commission adopted a new Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF). The TCTF is based on the crisis framework adopted by the Commission in 2022, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and consequent disruptions of markets and supply chains. The framework is aimed towards the renewable energy sector and increased investment in clean technology production in Europe, and forms part of EU’s European Green Deal, which is a holistic set of policy initiatives to boost the competitiveness of European industries as well as renewable energy supply, as Europe strives to be carbon neutral by 2050. The framework prolongs existing state aid measures with some amendments, and also introduces new state aid measures.

The EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA), which supervises Norway’s state aid compliance under the EEA Agreement, will apply the TCTF in full from the date of adoption by the Commission.

The TCTF i.a. gives the Member States, as well as the EEA EFTA States (including Norway), the possibility to grant state aid schemes to address the investment gap in sectors strategic to obtain a net-zero economy. This includes:

- Roll-out of renewable energy production and storage: All renewable energy sources are included, such as solar, wind, geothermal, biomass, and renewable hydrogen, as well as key types of energy storage.

- Industrial decarbonization: This includes electrification, energy efficiency projects as well as fuel switches to green hydrogen.

- Manufacturing of green technologies: This includes the manufacturing of relevant equipment such as batteries solar panels, wind turbines, electrolysers, etc., and key components for such equipment, as well as production or recovery of critical raw materials.

The aid may be provided as direct grants, or other forms such as tax advantages and subsidised interests rates or guarantees on new loans.

The aid intensity and maximal amount depends on the size, and for some of the schemes, also the location of the receiving undertaking, with the highest cap available for small and medium-sized enterprises.

We will in this article explore in further details some of the key implications of the proposal for the Norwegian economy.

Broadening the scope for state aid to wind production and operation

Notably for Norway, the TCTF expands the opportunities for granting aid to the wind power sector. Operators can receive aid both for investment and operation. No cap on the aid is set as long as a competitive bidding process is executed. The services industry can also receive aid within significant margins (more on this below).

This news is significant in a Norwegian context, as the Norwegian government announced the opening of the first two areas for commercial offshore wind production in Norway on 29 March 2023.

The state aid cap for one of the areas, Sørlige Nordsjø II, has been set at NOK 15 billion. This is pending approval from ESA, but in light of the TCTF and the existing 2022 Guidelines on State aid for climate, environmental protection and energy (CEEAG) there seem to be no major obstacles for an approval. In February, the Commission also approved EUR 2.08 billion (NOK 23,65 billion) in aid to a French offshore wind project. The pre-qualification process and the auction for an award of the current phase 1 offshore wind area at Sørlige Nordsjø II imply that the TCTF’s generous rules for aid granted through a competitive bidding process apply.

Aid for equipment and components

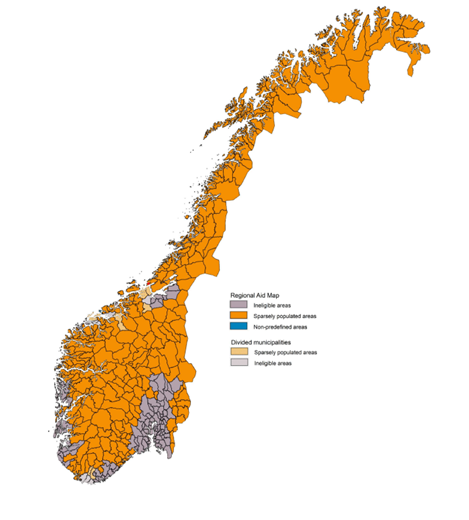

In addition to aid to energy production projects, the TCTF covers aid for investments in the production of equipment important for the transition towards a net-zero economy, including the wind service industry. The aid intensity may not exceed 15 % of the eligible costs and the overall aid amount may not exceed EUR 150 million per undertaking (group) per country. However, exceptions are made for projects in so-called ‘c’ assisted areas. In these areas, aid can amount to 20 % and up to EUR 200 million. Each EEA member states designates such areas. In Norway, these areas are sparsely populated or less economically developed areas, covering most of Norway:

If the aid incentivises the beneficiary to locate the investment project, or trigger linked investment projects in the assisted areas that are necessary for the production of goods relevant to the strategic sector, aid may be given beyond these limits as an extraordinary measure. Such aid can be up to what the project could demonstrably receive for an equivalent investment in a third country jurisdiction outside the EEA (the so-called “matching aid” regime), provided that the investment is located fully in these assisted areas. The “matching aid” regime is particularly important for projects that would be eligible for high subsidy levels in the USA under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The purpose of the scheme is to avoid production of key goods for the net zero transition being moved out of EU/EEA, while diversifying investments geographically.

Projects not locating investments in the assisted areas can receive matching aid provided that the investment is made in three different EEA member states, and a significant part of the capital investment takes place in at least two assisted areas. The aid is subject to prior approval and the amount of the aid cannot exceed the minimum amount needed to incentivise the beneficiary to locate the investment in the EU/EEA (the so-called funding gap).

It is somewhat unclear how the requirement that the aid must “incentivise the beneficiary to locate the investment project or to trigger linked investment projects” in an assisted area is to be interpreted. The main rule under the general guidelines on regional aid is that the aid can only cover the costs associated with investment and operation in and of assets located in the assisted area. The wording of the TCTF is somewhat wider, and in our view, this may indicate that it opens for the aid to also cover costs incurred outside the assisted area, e.g. cost of administrative resources, provided that the brunt of the investment is made in assets located in assisted areas.

Deadlines for aid

The aid under the new schemes in TCTF must be granted before 31 December 2025, and renewable energy producing installations receiving aid must be in operation within 36 months after granting of aid. Notably, however, the 36 month deadline does not apply to offshore wind installations.

Amendments to the GBER: now covering offshore electricity grids

In addition to the TCTF, the Commission has introduced several amendments to the General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER), which also facilitate public investments in renewables projects. The GBER sets out several categories of aid that are considered compatible with the TFEU and EEA agreement, provided certain conditions are fulfilled. While aid schemes falling within the scope of the TCTF must be notified to and approved by ESA, aid granted within the limits set out in the GBER is automatically permitted and does not require prior notification and approval.

An important change to the GBER is that the definition of “energy infrastructure” is amended to include offshore electricity grids that are subject to a third-party access regime. This means that state aid can be provided to electricity grids connecting offshore wind farms without notification to ESA, up to EUR 70 million per undertaking per project.

Conclusions

The changes to the European state aid regime significantly broadens the scope for governments to grant targeted state aid to facilitate investments that can contribute to reaching a net-zero economy by 2050. With the significant investments needed to finance this major shift, state aid can make the difference between whether this goal is reached or not. Knowing the implications of the new framework will be important both to authorities and businesses within the relevant sectors who are looking for potential sources for funding for their projects.

The new framework has the potential to boost investment in e.g. offshore wind power production and other new green industries and technologies in Norway, where the public and private sectors work together towards the common goal of net zero. On the other hand, if Norway chooses not to put funding behind the opportunities, and to use the temporary opportunities, we may see investments leaking to countries providing more generous state aid to exploit the opportunity to accelerate the green shift even further, particularly the US – as they have due to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA. Even though the TCTF has rules designed to avoid relocation of existing industries between EU/EEA countries, it is the location of new industrial opportunities that the green shift generates that is the biggest concern. If Norway does not swiftly follow up on the developments coming from the EU, we may lose significant industrial opportunities also to other European countries.