Sørlige Nordsjø II and Utsira Nord: Comments to CfD auction and support scheme

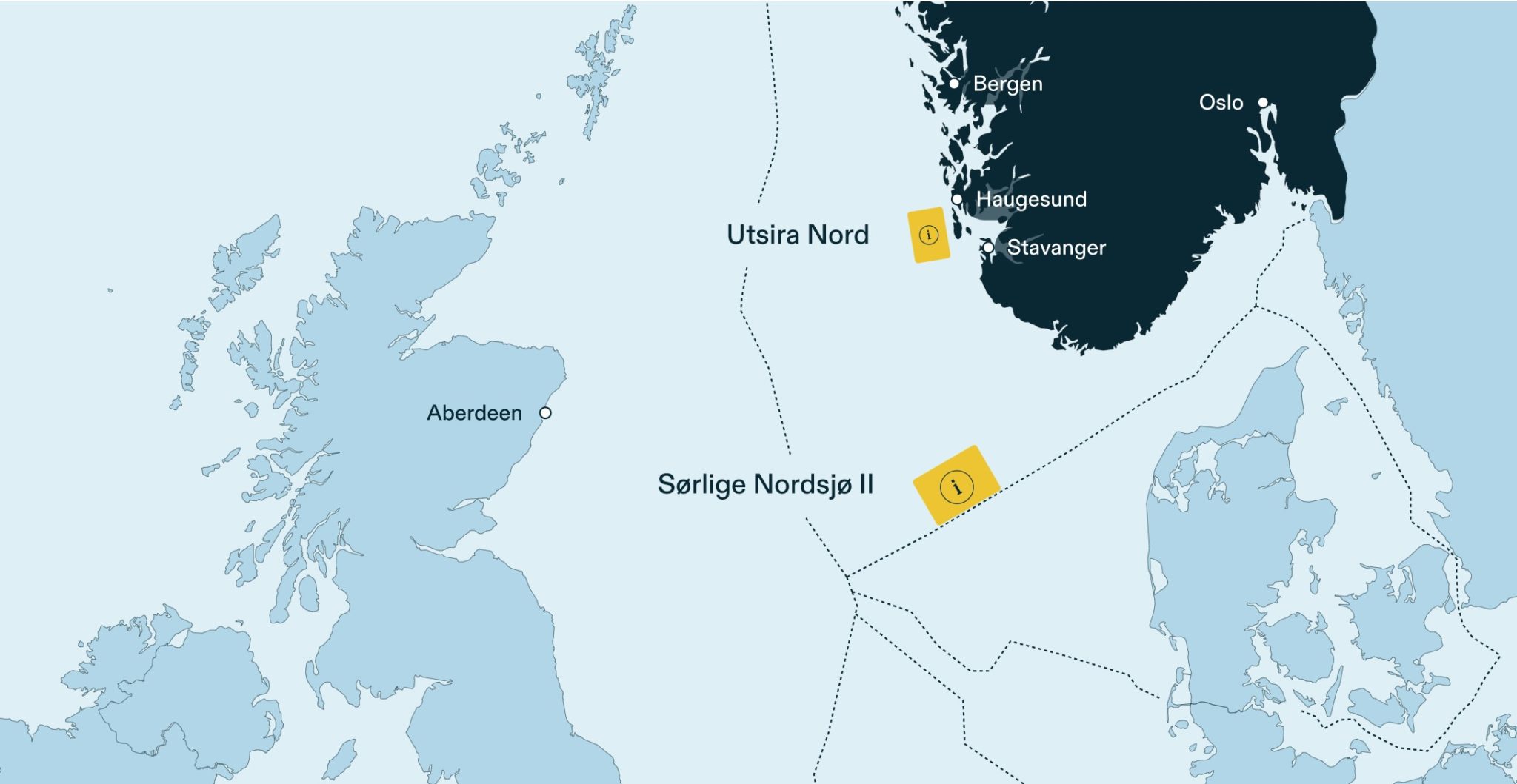

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy’s (the “Ministry”) announcement of the final competition rules for the Sørlige Nordsjø II (“SN II”) and Utsira Nord (“UN”) offshore wind areas is as mentioned in our news from 29 March 2023 broadly in line with the consultation documents from the hearing rounds in December 2022 (the “Consultation Papers”). However, there are still some important changes and clarifications worth addressing.

On 30 March 2023, the Ministry also presented a proposal for authorization for support for renewable energy production at sea for the first phase of Sørlige Nordsjø II (prop. 93 S “Authorization to enter into a bilateral contract for difference for support for renewable energy production at sea from the first phase of Sørlige Nordsjø II”) (hereinafter “Prop 93”), that provides some further clarifications and details regarding the financial support schemes and the auction proposed for SN II.

In this letter, we will focus on the auction process for SN II and the competition on governmental support scheme at UN, on a high level and with a focus on what has been clarified or amended since the Consultation Paper in the announcement from 29 March and the following issuance of Prop 93.

The (i) grid solutions and (ii) the criteria for pre-qualification on SNII and the qualitative criteria for UN will be commented upon in separate news articles. Comments on the criteria will be published soon.

There are no major changes to the overarching approaches to the two areas. SN II remains an auction with pre-qualification criteria and UN, remains a competition on qualitative criteria with a subsequent competition on governmental support scheme.

As expected, the auction for SN II and the competition on governmental support scheme for both project areas will be a two-sided contract for difference contract (“CfD”).

SN II

For SN II, only the applicants that have been successful in the pre-qualification rounds are eligible to participate in the CfD auction. The Ministry have stated that there is a minimum of six and a maximum of eight applicants who may participate.

The Prop 93 requests authorization from Parliament to enter into a two-sided contract for difference contract for renewable energy production with a reservation price of NOK 0,66 pr kWh. No bids above the reservation price will be considered. The auction model is a British auction with open bidding. In case of a draw, the highest score in the pre-qualification will prevail. The reference price will be tied to price area NO2 and will be on a monthly average. There will be a minimum price for support of NOK 0,05 pr kWh. The validity of the CfD will be for 15 years, starting at commissioning. The maximum amount for subsidies under the CfD will be NOK 15 billion. The maximum amount will be mirrored for payment from the developer to the state. The CfD is limited to a capacity of 1400 MW, even if the developer chooses to construct an offshore wind farm with 1500 MW capacity. The surplus capacity will have to be delivered directly to the end-user and not through the onshore grid connection point or utilized in another manner.

There will only be one winner in the CfD auction on SN II and the winner will be the applicant with the lowest bid, i.e., the developer that is willing to develop SN II with the least amount of governmental funding. However, the score on the pre-qualification criteria will be decisive in the case of a draw in the auction. We note that the applicants should not under any circumstance take a light approach to the pre-qualification criteria.

The CfD contract, which will be non-negotiable, is not yet published.

UN

UN and the three project areas will be awarded to three applicants who receive the highest scores in the qualitative competition. Post award, the three successful applicants will compete for a support scheme where only two of the successful applicants will receive funding. Not much is known about the details at this point, but we do know that the support scheme will be based on a two-sided contract for difference for renewable energy production at sea, with a duration of 15 years. As for SNII, there will be a reservation price and a maximum limit for the support that will be available both through a monetary cap and that the support only will be available for 500 MW, even if the total production capacity will is increased to 750 MW. Except for high level information, detailed information on the CfD mechanism is not yet available, but the main principles applied for SNII will likely also be followed in the CfD for UN. Some exceptions may apply, e.g., in respect to the reservation price (which is based upon estimated Levelized Cost of Energy (“LCOE”)) and level of guarantees (reflecting the likelihood of payment from the developer to the state).

In the below, the main focus will be on SNII and the details laid out in the Prop 93. Further review of the detailed terms of the SNII CfD and on the frame for support on UN will follow when such information is released.

SN II – The Ministry’s assumptions for subsidies

The Ministry expects that SN II will not be profitable for the developer without subsidies. Mainly due to the depth of the SN II project area and the long distance to shore, which will entail high construction and operational cost that outweighs any profit from the expected price of electricity.

The Ministry is expecting in its basis-scenario that the level of subsidies needed for SN II, based on the expected development of the price of power and the estimated investment and operational costs, will be approximately NOK 9 billion. In its basis-scenario, the Ministry is assuming the total investment cost to be approximately NOK 40 billion for the construction of the offshore wind farm and the network solution up to the connection point in the onshore transmission network. Any construction contributions because of necessary reinforcements in the network on land are not included in the estimate. The operating and maintenance costs for the offshore wind farm and grid access are estimated at around NOK 750 million annually.

We note that these assumptions are at a high level and that there are multiple uncertainties that are challenging to consider, notably the expected high pressure on the supplier industry in a period until the suppliers have increased their capacity. We would also like to note that the assumptions presented above do not take into account the last two years’ price hike.

The estimated future pricing of electricity is uncertain. Statnett has estimated that offshore wind from SNII connected radially to Norway will achieve an average power price of 39 øre/kWh, with a range between 34 and 43 øre/kWh on average between 2026 – 2060.

Sensitivity analysis further shows that a 30% higher investment cost and a lower power price of 31 øre/kWh will result in a need for subsidies in the order of NOK 23 billion to make the project break even.

The high costs coupled with the uncertainty with regards to the future power price, support why the “ability to execute” criteria are weighted 60% in the scoring matrix for the pre-qualification on SNII.

SN II – ESA Approval

The EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA), which supervises Norway’s state aid compliance under the EEA Agreement, will have to approve the proposed subsidies and the Ministry has initiated the approval pre-notification process. There is a theoretical possibility that ESA might require certain amendments to the proposal. Although, approval is expected. In March 2023, the European Commission adopted a new Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF), which even widens the possibility to give aid to the wind power sector. Operators can receive aid both for investment and operation. There is basically no cap on the aid that may be provided if the award is subject to a competitive bidding process. We do expect that the proposed scheme, including the size of up to NOK 15 billion, will be approved, based on recent approved aid schemes for offshore wind developments.

SN II – Overview of the main principles of the CfD

The CfD is a common mechanism for providing support for development of offshore wind. Essentially it is a long-term agreement with the state that provides a guaranteed energy price (“contract price”), and hence covers the developer`s risk for energy prices below the contract price. The support provided in periods where the energy price is below the contract price is equal to the difference between the contract price and the energy price multiplied by the energy production in the same period. If the energy price is above the contract price, the difference/increased income becomes due from the producer to the state. Competitive bidding on the contract price is designed to minimize the level of support by creating competition between the pre-qualified applicants, where the applicant which requires the least aid (i.e., the lowest guaranteed energy price) emerge victorious. As a result, the project area is assumed allocated to the most cost-efficient project.

The state’s level of aid – and thereby exposure – under the CfD is limited by two mechanisms: 1) a reservation price and 2) a cap on the maximum of subsidies under the CfD.

Reservation Price

The Ministry has proposed a reservation price of NOK 0,66 pr kWh. This represents the highest price of energy that the state is willing to guarantee per kWh of the energy production. Any bid for a contract price above the reservation price will not be considered. A visible cap prior to the start of the auction sets the state`s expectations and lowers the risk of a high contract price. The Ministry’s proposal for a reservation price of NOK 0,66 pr kWh is based on NVE’s calculations on LCOE in a pessimistic scenario, with a margin of 15%.

Maximum of subsidies

The maximum amount for subsidies under the CfD is proposed to be NOK 15 billion. Besides management of its subsidy risk, the state requires a cap for budgetary considerations. The maximum amount will be mirrored for payment from the developer to the state.

It is worth noting how the Ministry calculates the maximum cap. The calculation is done on a net basis, so that the decisive factor is the size of the support given, minus the amount paid to the state from the developer, at any given time. Once the cap for support is reached, any further payments/support from the state are suspended until high energy prices result in payment from the developer to the state and the net level of support falls below the maximum cap. And vice versa, payments from the developer to the state will be suspended when the cap on payments is reached, until energy prices result in payments from the state to the developer and net payments from the developer to the state again is below the cap. Payment both ways can in a sense be revived during the full 15 years duration of the CfD.

We would like to note that according to the Thema prognosis presented in Prop 93, the price of power, is assumed to be generally high until 2032. Hence, the developer may have to expect to pay the state in the initial years of production. This applies even if the contract price is equal to the reservation price of NOK 0.66 kWh, as we note that Thema’s price prognosis forecasts higher prices than the reservation price in the initial years of the offshore wind farms` life. If the price of power remains high for a longer period, and does not fall below the contract price before toward the end of the 15-year duration of the CfD, developers should be prepared for not being able to recoup the payments made to the state, and at least not to benefit from any net support.

The forecasted power prices favour the state and one could argue that a longer period for the CfD would provide increased protection for the developer. Several hearing notes requested a longer CfD period. The Ministry points to CfD’s entered into in the UK and refers to their validity of 15 years as the main explanation for their decision. On the other hand, if the prices remain high the developer will benefit from the expiry of the CfD. Developers will also be able to hedge their risk if they enter into long term PPAs supporting their own LCOE beyond the term of the CfD.

Reference price and the relationship to the actual energy price achieved

For the parties to assess whether payments should be made from the developer to the state or from the state to the developer, a reference price will be established. In periods when the reference price is lower than the contract price, the state is obliged to cover the difference (price supplement). In periods when the reference price is higher than the contract price, the producer must pay the difference to the state (price deduction). In this situation, part of the income from power production will thus go to the state.

This also applies if the energy is sold at another price than the reference price, e.g., if the developer has entered into a private Power Purchase Agreement (“PPA”) with an agreed energy price that differs from the reference price, or if the actual spot price achieved at any time differs from the reference price. It has no impact on the state’s costs or income if the power is sold on a regulated power exchange or through a PPA. The decisive factor for the state’s costs and income is the relationship between the contract price and the reference price.

For SN II, the reference price will correspond to the monthly average price in price area NO2 and payment between the parties will be on a monthly basis. If the structure of the price area is changed within the CfD agreement period, the reference price will be based on the monthly average price in the price area the wind farm belongs to after the change.

The Ministry has in Prop 93 adjusted its proposal since the Consultation Papers, where it proposed a one-year average as basis for the reference price. Several hearing bodies pointed out that a long reference period would increase the risk for the producers and that the risk would translate into higher bids in the auction. By introducing a shorter period for calculation of the reference price, more of the short-term risk in the power-market is transferred to the state. The use of average prices means that the producer is protected against long-term fluctuations in the power price but maintains exposure to short-term fluctuations within the relevant month and hence also to the actual energy production profile. Some of this risk may be hedged by the developer if it enters into a PPA, but the developer will still be exposed to the risk that the reference price remains above the price agreed in the PPA.

Validity

In the Prop 93 it is stated that the support period of 15 years begins when the production and network facility has been built and put into operation upon “completion”. And that “completion” assumes that the “majority” of the wind turbines are connected and have delivered power. The Prop 93 goes on to state that any power production before the requirement for completion has been achieved does not give the state the right to payment, even if the reference price should be higher than the contract price.

One could argue that the above provides an incentive for the developer to not complete the offshore wind farm in the situation where the power price is so high that it outweighs the penalties the state can impose for late completion. At present, we do not have access to the detailed provisions regulating the “completion”, nor the regulation of penalties for delayed completion, but the regulation as presented thus far might have a potential for the developer to be influenced by other interests than the interests of the state, which is to have the complete farm in operation as soon as possible. That said, if the prices indicate that the developer will be eligible for payments from the state from the very start of production this will not become a concern, and in any event might a speculative approach from the developer’s side lead to grave consequences as the CfD also regulates that delay above a certain threshold will result in a reduction in support period and potentially also the right for the state to terminate the CfD agreement.

Cessation of support at low prices / minimum price and relief

The minimum price for support is in Prop 93 set at NOK 0,05 kWh. This is according to the Ministry to discourage the wind farm from producing power at times when the value of production is negative. Such limitation is in line with EU legislation on state aid.

Conversely, there might be situations where it is desired from a state perspective that the wind farm produces power, even though the producer is in a situation where it produces at a loss due to the spot price and the payments to the state. In these situations, the Ministry will propose relief in the level of the amount the producer will have to pay to the state to ensure that the production is not suspended.

Developers should account for both these measures when considering how to structure a potential PPA.

Inflation adjustment

As a main rule, there are no inflation adjustment for the investment and operating costs in line with the support and risk profile in the CfD. The state will only share power price risk as stipulated above, but all other cost risks are as a main rule the developers to carry alone. In Prop 93 there is, however, proposed an exception with respect to 1) the contract price, 2) the minimum price and 3) the maximum cap for total payments between the parties to the CfD. The inflation adjustment will be based upon the consumer price index with effect from Q1 2024 until Q1 post completion and commissioning.

We note that this remedies some of the inflation risk associated with the initial CAPEX investment, assuming that the contract price offered from the developer has been set based on its estimated LCOE, of which the initial CAPEX investment is a material part. Hence, the inflation adjustment will increase the contract price, which, again, to a certain extent alleviates the risk of when the developer must pay to the state and increases the possibility of when the developer is eligible for support. Simultaneously, the cap on payment to the state is increased equal to the cap on support, implying that if the developer has been willing to “buy” the exclusive rights to develop the area, through offering an unrealistic low contract price in the auction, the total price for the exclusivity may increase from the initial NOK 15 billion.

Guarantees

The state will require several guarantees from the applicants. In the actual pre-qualification and auction process and during the development and operational phase.

Firstly, the state will, as a requirement for the pre-qualification process require an on-demand guarantee for NOK 400 million from all potential applicants. The on-demand guarantee must be in place no later than 14 days prior to the auction. The guarantee stipulates that if the successful applicant has not within four weeks from the finalization of the auction, a) formed a corporation in line with the Offshore Energy Act §3-5 and b) entered into the CfD agreement and c) provided further guarantee for the developer’s obligations under the CfD, then the state can call on the guarantee.

It is not clear what level of guarantees are required under the CfD, except that the state requires securities for the developer’s obligations towards the state under the agreement. As stipulated above, the developer potentially has an obligation to pay up to the cap of NOK 15 billion. In addition, there are multiple penalties and other obligations that the developer may be responsible for under the gurarantee. The guarantee for the obligations under the agreement will apply as long as the CfD agreement is in force and will be in addition to any guarantees made under the Offshore Energy Act.

For example, guarantees for removal costs at the end of the concession period, long after the agreement has expired, are required under the Offshore Energy Act.

We note that the possible level of guarantees that are required, potentially is very high and we expect that surety of the levels of guarantees required are of high importance to the potential applicants.

Various scenarios that can affect the costs, responsibilities and risks in the CfD

a) Concession after the Offshore Energy Act

There is no automatic right of concession after the developer has won the auction. The Ministry states in Prop 93, that if the developer is not granted a concession, then both parties are relieved of their obligations under the CfD and the agreement is deemed void. It is unclear if there will be any penalties or other recourses applying if the developer can be blamed for not being granted a concession and the project not being executed.

b) Delay and breach

Delay in completion will, as a main rule, be sanctioned by the state by way of liquidated damages. The state will, however, not enforce any penalties if the developer is delayed due to reasons of the state in the concession process.

The producer carries the risk for available capacity at the connection point in the onshore grid. The state, however, and as for the concession, will not enforce any penalties if the developer is delayed due to the lack of capacity at the grid connection point.

Upon breach of contract from the producer during the CfD period, the state has the right to reduce the level of support from the state to the developer. In case of material breach, both parties will have termination rights. If the producer cancels the project, or if it is clear from the developer’s actions or omissions that the energy plant will not be established, the state can demand a pre-determined penalty. It is yet not clear what this penalty will be.

c) Transfer of the network facility

From the outset, the developer is responsible to construct and maintain the network facility up to the onshore connection point. The CfD contains a right for the state to take over ownership of the network facility on more precisely determined terms. When taking over the grid system all responsibilities will be taken over by Statnett or the state. On what terms such transfer of ownership will occur, will be of high interest to the developer but can only be assessed once the CfD agreement is made available.

Comments on the auction

In the Consultation Papers, the Ministry seemed to lean towards an Anglo-Dutch auction model where the auction would be open until two bidders remained. The last two bidders would then deliver a closed bid. This was addressed in the hearing round by multiple parties and has been amended to a pure open British auction. In case of a draw, the score on the pre-qualification criteria will be decisive.

We note that the further details of the auction process will be of interest as the application of the British auction can have an impact on the bidding strategy. We are uncertain as to whether the auction will have rounds whereby the bidders will have to ascertain whether they will participate in the next round (i.e., be willing to offer a lower bid than the lowest bidder from the previous round) or if it will be conducted differently, e.g., by a classic auction where bids are submitted consecutively until no one is willing to lower their bid. If the scoring or ranking from the pre-qualification is known to the bidders prior to the bidding (e.g. because someone have been excluded from the auction to reach a maximum of 8 bidders), a classic auction process might lead to strategic bidding, whereby a bidder with a high score/ranking can speculate in not entering the auction before late in the process and limit its bid to match the lowest bid. The further announcement of the detailed auction rules is planned for August this year.

UN – competition for support scheme

We refer to what is stated above in the introduction section in this paper. As a general comment, it is widely accepted that the LCOE will be higher for UN than for SN II, and hence that the need for state aid is higher for UN than SN II. Therefore, one might assume that the reservation price will be set higher than the NOK 0,66 pr kWh set for SN II, that the offered contract price will be accordingly higher than for SN II and hence that the likelihood of the developer paying to the state is less compared to SN II. This may again impact on the requirements that the state will define with respect to guarantees that the developer must provide.

Further, in the Consultation Papers, a collective industry has questioned why only two of the three successful applicants will be granted support. Although we do not pretend to know the thoughts of the Ministry, there is a possibility that the qualitative competition – as opposed to the pre-qualification with an auction on SN II – does not alone satisfy the criteria for state aid if there is no trace of a competitive bidding process for the support. However, this remains pure speculation as we do not have enough details on the planned support scheme.

The project that does not receive state funding will retain the right to the project area for a period and may use the general public support system and might become eligible to participate in possible future competitions for support.

Summary and Haavind comments

The period for clarifications to the announcement is 17 April – 1 June with the application deadline being 4 August. As shown above a deep understanding of the CfD is hard to achieve without the actual agreement. It would be beneficial for all parties concerned if the agreement was made available as soon as possible. We also note that it will be of great importance to most developers to know the specific amount applying for any of the guarantees to be provided by the successful bidder. In addition, it will of-course be necessary to know all details regarding the grid-system requirements to be able to actually estimate the LCOE in order to calculate the contract price.